Food for the Spirit

Reflections on life, love, art, beauty, etc.

In the summer of 1971, Adrian Piper embarked an ambitious experiment. Self-isolating in her New York loft, she dedicated herself to an ascetic lifestyle, reading Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, practicing yoga, writing, and fasting. As a result of her complete engrossment in Kantian thought, she “began to disassociate and question her material existence.” From time to time, she photographed her reflection in a mirror to reaffirm herself of her physical being, while chanting phrases excerpted from Kant’s Critique. This project—preserved through Piper’s ghostly photographs—is an essential work of conceptual art.

50 years have now elapsed since Piper performed “Food for the Spirit.” Although I do not have the mental resolve (or desire) to commit myself to a re-enactment of her experiment, I cannot help but feel the primacy of Piper’s work in 2021, particularly at the onset of a second summer of forced quarantine. Spending most of my time in the digital vortex, I find my experience so concentrated in the mind and dependent on ocular stimuli that I too, like Piper, question the materiality of my existence. My stomach lurches and my eyes burn from overuse. I struggle to wade through my mind-muck. The digital lag of click-scroll-swipe seems to imprint itself onto my mental processing of things, eroding my feeble attempts at mindfulness and dulling my wits. Once I fall into the vortex I can’t seem to claw my way out. I mime the behavior of a video game addict, playing past the point of enjoyment even as I feel myself wasting away.

To be clear: I don’t mind dis-identifying with my body, but I want it to do it for the right reasons, and under my own terms. Like Piper fifty years ago, I want to find transcendence in willfully phasing out of my body.

I recently read All About Love by bell hooks, recommended by a close friend. Like many others, I found myself enthralled by hooks’ writing, and was especially drawn to her rhetoric of spirituality. For her, love and the spirit are inextricable. She asserts that our culture is loveless, in part because of the commodification of spirituality.

For much of the pandemic, I have often felt terrified by my lack of emotion and heart. When was the last time I had cried? Too long ago to remember. I find myself navigating the world at a remove, going through the motions of life robotically. I attribute this emotional deficit, in addition to being an instinctive act of self-defense, to my being out of touch with the inner self—that is, my spirit. At some point, I had stopped believing in the non-visible forces animating living beings, instead favoring the pragmatism and rationality of my Western education.

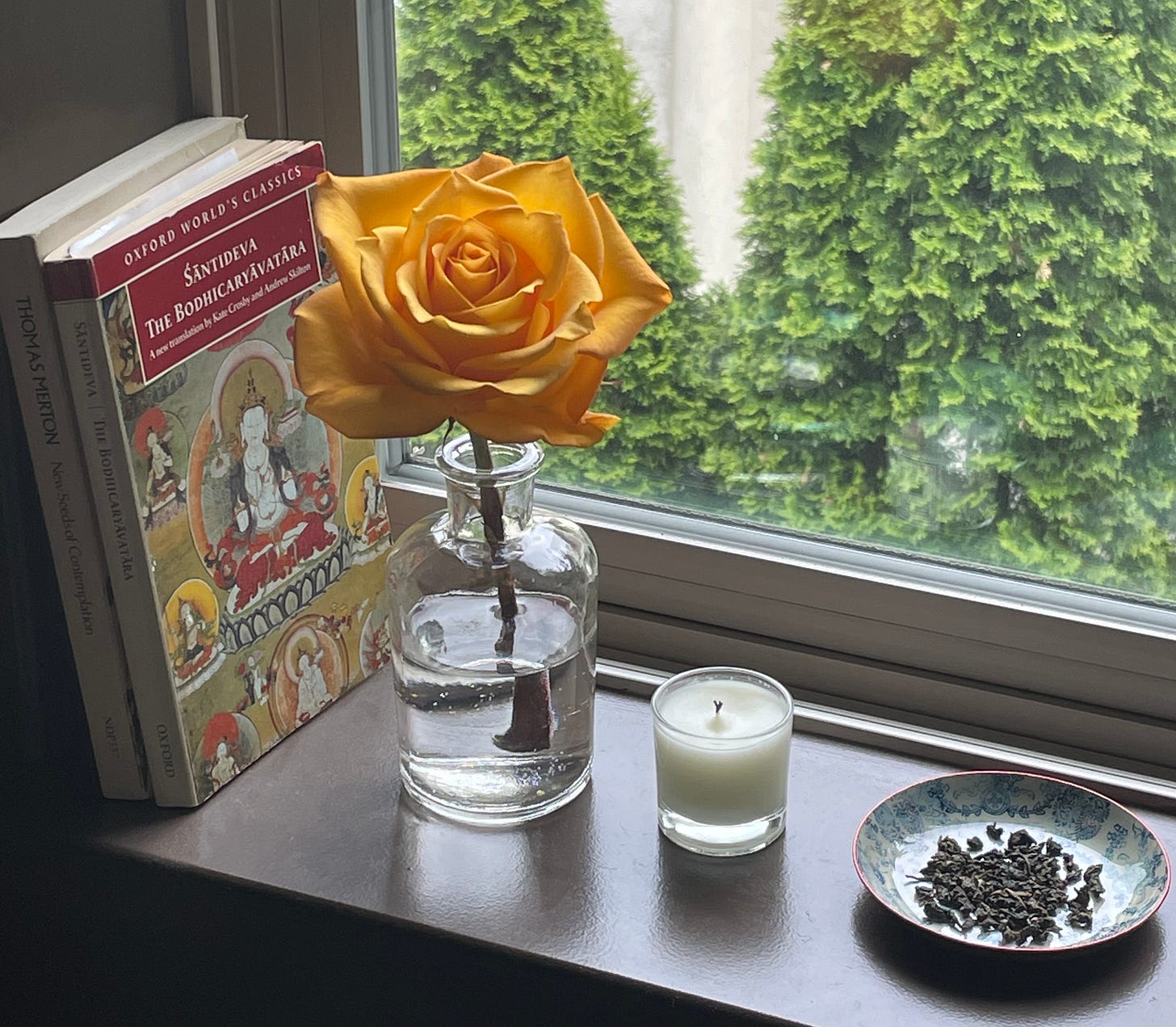

Reading hooks, I wanted to reincorporate spirituality back into my life. I grew up going to church, and in some ways I’ve never really outgrown the need to orient around something or someone greater than myself. Spiritual practice, according to hooks, does not need to be governed by organized religion, as it is not the institutionalization of spirituality that makes it meaningful. Rather, spirituality means learning to escape the confines of our bodies, which often limit our mental and emotional development, and strive for an experience of life that finds transcendence in banality:

“When we begin to experience the sacred in our everyday lives we bring to mundane tasks a quality of concentration and engagement that lifts the spirit.”

This active seeking of the sacred is necessary in a society that constantly tests our capacity to love, hijacks our attention and desires, and subjects our individuality to the same laws and forces applied to objects in the all-consuming conquest of capital. In a system which treats bodies the same as objects, spirituality allows us to rediscover our humanity.

To be frank, I’m not entirely sure what form each of my meditations will take, but I hope to provide food for the spirit, engaging with texts (interpreted broadly) that have been nourishing for me, in hopes that they will provide sustenance for others as well. I am also interested in continuing hooks’ investigation of love—what is this mysterious substance that binds us together, and how do we preserve it when external forces seem intent on tearing us apart? I don’t know, but I sure hope to find out someday.

I also want to credit several friends who have inspired me:

Wendi, whose updates now serve as a time-capsule for her incredible gap year;

Tai, whose generous spirit nourishes and vivifies in both spoken and written word;

Dan, whose critical reflections on technology are informative, thoughtful, and timely.

Subscribe to get notified when I write something new (I can guarantee inconsistency) >>